Hell behind the screen: cyberviolence is turning into digital weapons in Benin

In Benin, cyberviolence is exploding on social networks and turning smartphones into emotional battlefields. Behind every hateful message are victims, often women, sinking into fear, shame, or silence. While the Centre national d’investigations numériques (CNIN) tries to contain the scourge, even journalists investigating the issue face insults, threats and smear campaigns. This invisible harm crosses screens and attacks the soul.

It often starts with a harmless vibration. A notification, then another, and another. The words scroll by, seemingly harmless, before turning into sharp blades disguised as insults, mockery, threats. Behind avatars and pseudonyms, hate pours out and erases the boundaries between the virtual and the real.

In Benin, as elsewhere, women are the primary targets. Because they dare to speak, assert themselves, occupy public spaces long reserved for men. The attacks take the form of body shaming, threats of rape, sexual blackmail, or reducing a woman to her body. Social networks thus become the extension of a patriarchy that mutates, digitizes and strikes in silence.

For Valdye Gbaguidi, a young content creator, hell began the day she dared to tell her story. An activist for body positivity, she promotes acceptance of all bodies, whatever they are. “Body positivity is acceptance of all bodies. We must respect differences without judging or sexualizing,” she explains in a soft voice.

But the Internet gave her no respite. “I said I had been raped when I was younger. I wanted to understand my wounds, help others speak. Instead of support, I got insults. Some said that, given my body, it was normal that I was raped. Others mocked my chest.”

And everything turned on one evening in December 2024 at the Open Conscience Awards night. “I was a victim of body shaming and sexualization. I came in a dress, a beautiful pink dress, which, by the way, my parents saw and really liked because the dress suited me very well. And already on site, before going on stage, when they called me, I saw a look of disgust on the jurors’ faces that I didn’t understand at first,” the young Valdye recounts.

“The jurors lingered on my body shape and my style of dress and told me how much I deserved to be harassed. He went further and said, for example, that my chest didn’t displease him at all, that I had put it forward so people could see it and that he had seen it and that, moreover, he wanted to fall on my chest and maybe even go lower”, she added.

While investigating cyberviolence, we quickly understood that words can also wound the people they’re told about. Behind our camera and our notes, the fear of becoming a target ourselves was never far away. Words hurt more than a blow. They seep into the flesh, imprint on memory, and destroy self-esteem.

“Yes, I cried, I cried a lot, I cried all the time,” she confides. “I told my mother I wanted to have surgery. I couldn’t stand my body anymore. Social media was supposed to help me feel better… but it became a prison”, confessed Valdye. The filming scene was so moving that even the journalist had tears in her eyes, which she hurriedly wiped away discreetly with the back of her right hand so as not to attract attention.

Harassed, threatened, broken and silenced

These violences are not only emotional. They trap victims in a cycle of humiliation and isolation. Some drop out of school, others delete their accounts, others lock themselves away in shame.

Clinical psychologist and art therapist Stéphanie Gbéhounhessi, from the Art et Vivre practice in Cotonou, regularly sees young women in distress. “A student I worked with was labeled a loose woman online. Rumors spread through her university. She stopped attending classes. Her parents were helpless.”, the psychologist revealed. For her, the first step to healing is digital distancing. “You have to cut off from social networks for a while. Reconnect with real contacts, rebuild self-esteem. Without that, it’s impossible to rebuild,” she advised.

Then comes reclaiming the body through therapies based on art, writing, music or dance. “Resilience,” she says, “isn’t a slogan. It’s a slow process, made of scars and small new beginnings.”

The CNIN, last digital bulwark

In the CNIN offices in Cotonou, the tension is palpable. Screens display alerts, maps of suspicious connections, reports. Its director, Dr Ouanilo Mèdégan Fagla, is caught between urgent calls. “Here, for example, it’s a woman harassed online. Someone is sharing her intimate photos”, he explains.

“We receive at least fifty complaints a day. Depending on priority, severity and impact, we assign each case to an investigation team. The most serious cases are passed to the judicial police.”

He describes sextortion as one of the most violent forms. “It’s blackmail based on intimate images obtained deceitfully. Some perpetrators threaten to publish the videos to get money or to take revenge.”, he specifies. The CNIN does not limit itself to repression; it also runs awareness campaigns with the Agence des Systèmes d’Information et du Numérique (ASIN) and local NGOs.

“Prevention is essential. If women no longer fear reporting, we will have taken a big step,” concludes Dr Ouanilo Mèdégan Fagla.

The legal framework in brief

- The Beninese Digital Code punishes electronic harassment with one to two years in prison, and fines up to 10 million FCFA.

- Penalties are increased if the victim is a minor or vulnerable.

- Jurist Julien Hounkpè deplores judicial slowness: “You have to prevent before punishing. Train magistrates, strengthen international cooperation.”

But sociologist Bruno Montcho reminds us the problem goes beyond the law. “Cyberspace has no anchoring in our traditions. Our values promote respect and dignity. You can’t hide behind a screen to humiliate someone,” he emphasized.

Being a woman journalist is double exposure

Investigating cyberviolence is walking a tightrope between truth and fear. During filming, every interview, every exchange reminded us of the fragility of our own safety. The most sensitive interviews were scheduled in discreet locations to protect survivors’ identities. Some women agreed to talk but not to be filmed, for fear of being recognized and harassed again. Even when we accepted an anonymous interview, they sometimes refused at the last minute.

Precautionary measures went beyond the simple professional framework. “Journalists covering digital violence must be protected as much as their sources. Cyberharassers don’t hesitate to hack or stalk.”, recommended an expert from the CNIN.

Beyond technical risks, there was fear. The fear of becoming a target in turn. “When I read some hateful comments aimed at other women, I wondered: what if tomorrow it’s me?”, wonders Angèle, her voice full of emotion. This omnipresent doubt nevertheless fueled the determination to continue the investigation. “I understood that we had to see it through. If we, journalists, give in to fear, who will tell their stories?” she asks.

These tense moments reinforced the belief that field journalism now requires cybersecurity tools, emotional management and professional solidarity. For Angèle, being a woman journalist means existing against the current. “Every piece on GBV can trigger a storm of sexist insults, which is why since the rape case involving a minor and C. A. I avoid getting involved. I prefer to wait for the trial and listen to the testimonies of the parties concerned.”

Journalist Angèle didn’t mince words in denouncing the treatment of women journalists who cover GBV topics. “You’re dramatizing!”, “No one forces you to be on the Internet”, “You’re seeking visibility”, she fumed.

“Our women journalists suffer gendered attacks, remarks about their appearance, doubts about their competence. I plan to launch an awareness campaign on digital security and the psychological well-being of women journalists and GBV survivors”

At TRIOMPHE MAG, management acknowledges that the digital security of women journalists remains a challenge. “We’re working to strengthen our digital security measures, but resources are lacking”, explains the Publishing Director. “We encourage our journalists to report any cases of harassment, but many prefer to stay silent out of fear of judgment or stigmatization.”, he added.

For her part, Beninese journalist Angéla Kpéidja is not out of her troubles. The first Beninese journalist to openly denounce workplace harassment in May 2020, she still carries the aftereffects of that boldness in breaking the silence. Today, she has become the target of all attacks on social networks. “I can no longer stand the gossip and cyber harassment I’m subjected to”, the author of Bris de Silence expressed, distraught.

Train, equip, unite

Newsrooms are beginning to become aware of this systemic violence. Some are planning listening cells or training in collaboration with the Union of Media Professionals of Benin (UPMB), but many women journalists still feel their media outlets are not safe spaces to speak out.

This is what journalist Zakiath Latoundji, president of the UPMB, is doing through her project “Media without Violence”, which aims to strengthen the capacities of women media professionals to face GBV. According to her, the goal is to improve women journalists’ knowledge of the institutional and operational mechanisms for reporting, detecting and preventing GBV.

“It is also about promoting a culture of reporting GBV acts and overcoming shame and fear through the establishment of focal points and a GBV reporting committee”, she clarified.

Cyberviolence targeting women is not only more frequent, it is also crueller. Researcher Aïssatou Tchibozo, a specialist in gender and digital media, explains that “men receive criticism about their ideas; women, about their bodies. Threats of rape or public humiliation are weapons to silence them.” According to her, “every woman who is silenced by fear is a civic voice that disappears.”

When speaking becomes an act of courage

In Parakou, Cotonou or Djakotomey, victims still hesitate to file complaints. Some fear being judged, others fear being exposed again. This is the case of Nadia Okoumassoun, president of the NGO Femmes Capables, who in 2021 spoke out about the rape she suffered.

Today, she refuses our request to testify. Because of her professional career, she prefers not to reopen that dark past which could awaken old demons and, worse, remind her how at the time she was accused of being the sole person responsible for the rape she suffered. Valdye, however, decided to turn her pain into strength. For her, the media are a safe space to speak out and show a path to those who still lack courage. “No, I don’t regret having spoken. Because my story may have helped someone else speak”, she says.

On her page, she posts messages of encouragement, links to associations and the CNIN phone numbers. “Your body is not a shame. Your voice is a strength. Even if you tremble, you must speak.”

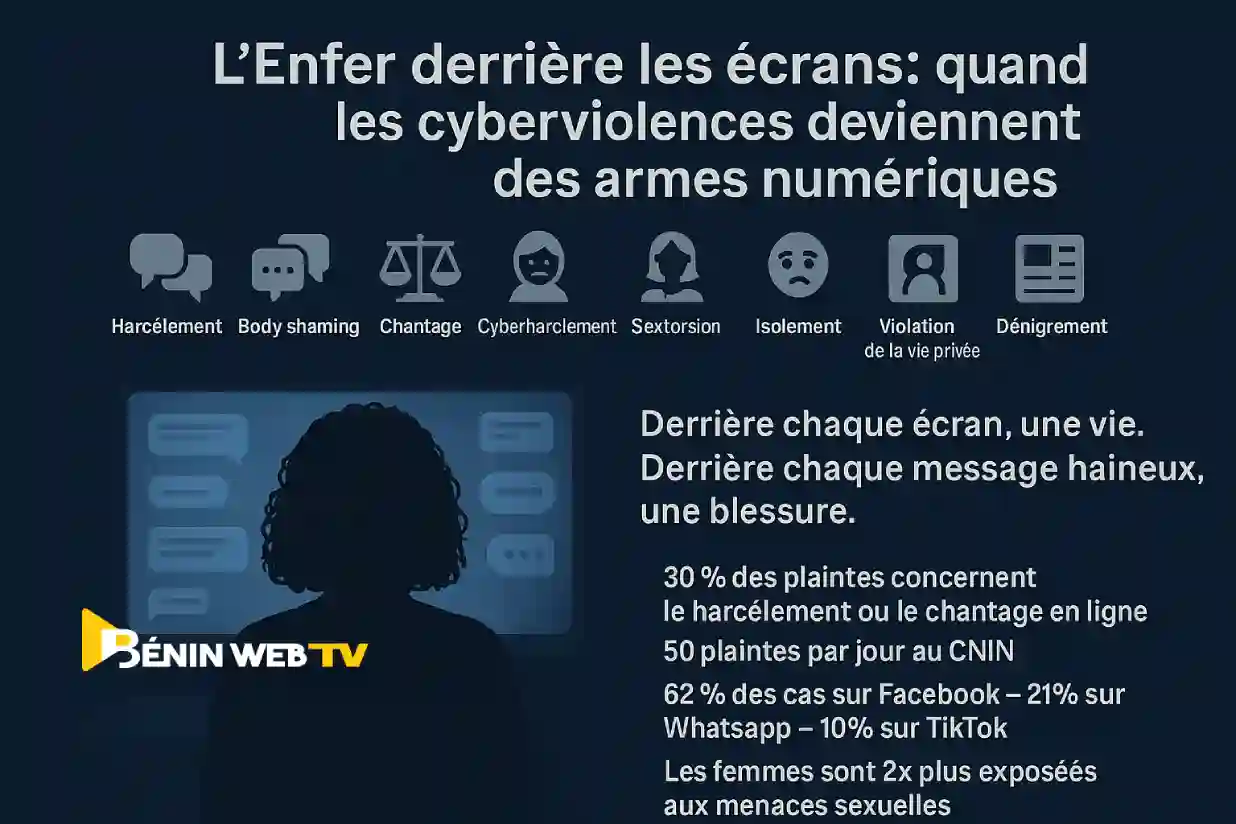

The worrying figures

- According to Commissioner Modeste Dossou Koko, head of the northern unit fighting cybercrime, 30% of complaints concern online harassment or blackmail.

- At the Centre national d’investigations numériques (CNIN), created in 2023, more than 50 complaints are recorded every day.

- Most cases involve sextortion, body shaming or the non-consensual sharing of intimate images.

- The CNIN collaborates with the judicial cybercrime police to bring perpetrators to justice.

- According to UNICEF (2019), one third of young Africans have been victims of cyberbullying.

- Women and girls are twice as likely to face sexual threats.

- The social networks most cited in complaints: Facebook (62%), WhatsApp (21%), TikTok (10%).

- Fewer than 20% of victims file complaints, for fear of social judgment.

- According to UN Women, 38% of connected African women have already experienced some form of online violence, a figure close to the global average (40%).

Speech as a weapon of resistance

Some days, rereading the threats received by our interlocutors was harrowing. In this context, journalism becomes an act of resistance. “We must give a voice to those we try to silence,” a colleague writes.

Today, Valdye continues to publish, more at peace. The scars remain, but fear has receded. She embodies a generation of Beninese women who refuse to be silenced, even behind a screen.

Behind every screen, there is a life. Behind every hateful message, a wound. Cyberviolence is not only virtual; it is social, cultural, deeply human. And for those who, like Valdye or women journalists, choose to speak despite fear, speech becomes an act of resistance, a light in the digital din.

- According to UNICEF (2019), one third of young Africans have been victims of cyberbullying.

- Women and girls are twice as likely to face sexual threats.

- The social networks most cited in complaints: Facebook (62%), WhatsApp (21%), TikTok (10%).

- Fewer than 20% of victims file complaints, for fear of social judgment.

- According to UN Women, 38% of connected African women have already experienced some form of online violence, a figure close to the global average (40%).

Speech as a weapon of resistance

Some days, rereading the threats received by our interlocutors was harrowing. In this context, journalism becomes an act of resistance. “We must give a voice to those we try to silence,” a colleague writes.

Today, Valdye continues to publish, more at peace. The scars remain, but fear has receded. She embodies a generation of Beninese women who refuse to be silenced, even behind a screen.

Behind every screen, there is a life. Behind every hateful message, a wound. Cyberviolence is not only virtual; it is social, cultural, deeply human. And for those who, like Valdye or women journalists, choose to speak despite fear, speech becomes an act of resistance, a light in the digital din.