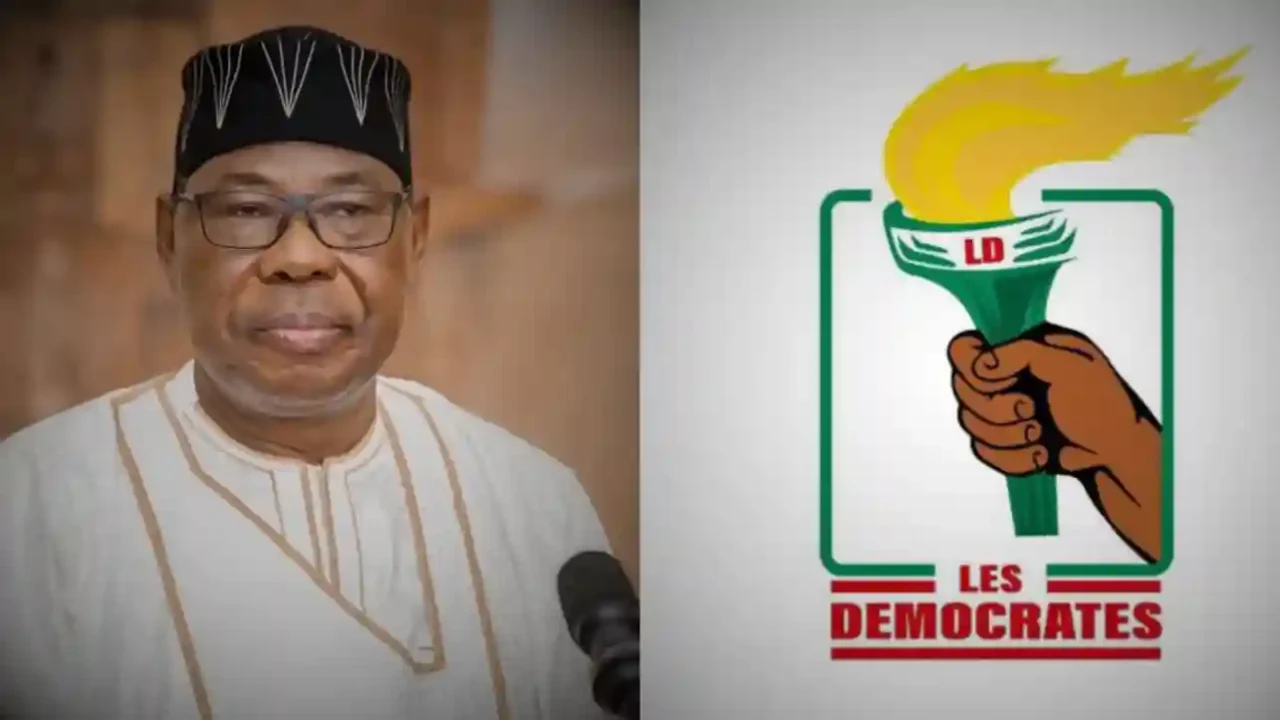

2026 presidential election: The Democrats face their perpetually thwarted destiny

The scenario seems to be repeating itself, relentless, almost prewritten. As the 2026 presidential election approaches, the party Les Démocrates (LD), the main opposition force, is once again mired in a political and judicial storm it struggles to escape. This Wednesday, the summons of the party president, Boni Yayi, and of the pair of candidates designated by the leadership of the judicial police revived old memories. Officially, the grounds are not yet known. Unofficially, everything suggests the matter is linked to the now-famous endorsement form confiscated by MP Michel Sodjinou, a file that is now at the heart of a dispute before the Constitutional Court.

The similarity with 2021 is striking. At the time, Les Démocrates’ candidate, Reckya Madougou, had her candidacy invalidated before being arrested and sentenced to twenty years in prison for endangering state security. Four years later, the story seems to follow the same contours, except that this time it is the party itself that could be declared ineligible, before its leading figures are tainted by new prosecutions.

How are we still here? That’s the question haunting observers of Beninese political life. Since the advent of the endorsement system, every presidential election has become for Les Démocrates an obstacle course where political strategy runs up against legal reality. In 2021, the party failed to maneuver in time to obtain the necessary signatures. In 2026, it seems to be repeating the same mistake, this time through an internal rift.

Because it all starts with a gesture. That of an MP, Michel Sodjinou, who refused to hand over his endorsement form, thereby depriving the party of the legally required number. Behind this refusal, he cites reasons of principle: contesting an internal process he deems opaque and clannish. But inside the party, many see it as a politically guided blow, a betrayal that comes at the right moment to disorganize the opposition.

The justice system is now involved. The Constitutional Court, seized, must say whether the list of endorsements submitted by Les Démocrates is valid. If it upholds the tribunal’s decision recognizing the validity of Sodjinou’s withdrawal, the party would automatically lose its ability to take part in the presidential election. And it is in this heavy atmosphere that the judicial police summoned the main leaders. A sequence which, beyond the legal aspect, points to a much deeper political issue: the place of the opposition in Benin’s post-reform political system.

Since 2019, electoral reforms have deeply reshaped the party landscape. They have brought greater political discipline, but have also raised many technical hurdles that require a fine mastery of procedures and internal balances. From the presidential movement to small emerging parties, all have managed to adapt, sometimes by forced march. All, except Les Démocrates. At every election, the same mechanism of failure repeats, as if the party refuses to learn from its setbacks.

Is it amateurism or a political curse? Some point to a lack of cohesion, a party trapped by its past and its internal rivalries. Others, more critical, suspect a targeted campaign by those in power, a system designed to neutralize any credible opposition even before the vote. Between these two readings, the truth probably lies in the complexity of Beninese political maneuvering, where law, strategy and loyalty often blur into a battle for survival.

But beyond the interpretations, one fact imposes itself: Les Démocrates find themselves once again on the edge of the abyss. Months before the ballot, the party presents the spectacle of a divided, weakened opposition now exposed to legal proceedings whose outcome no one can predict. If the Court confirms the disqualification, Sodjinou’s prophecy — that the party should forget the presidential election and focus on the legislative one — will be fulfilled in all its cruelty.

At this stage, it’s no longer just a procedural debate, but an existential question for the opposition.

In this affair, everyone will find their culprit: the reforms judged too restrictive, Boni Yayi’s governance judged too vertical, Sodjinou’s supposed disloyalty, or the relentless strategy of those in power. But at heart, the real question remains: does Benin still have an opposition capable of turning outrage into an alternative?

The answer may be decided this Monday, in a chamber of the Constitutional Court. If the decision is unfavorable, Les Démocrates will go down in history as the party that failed twice to cross the threshold of the presidential ballot. And this time, it won’t be the system’s fault, but that of its own demons.

Comments